1.

I’m going to start off with a personality quiz.

I once had a professor who liked making pronouncements and declarations. I appreciated this about her. It was a relief after years of soft, student-led pedagogy where we’d break into groups and discuss readings we hadn’t done. When someone turned in a story with a word like “chuckle” or “atop,” she’d scoff. “Nobody says that in real life,” she’d say, and then make them change it.

This professor told us that there are two kinds of people, or, at least, two kinds of writers: those who use lots of metaphor, and those who don’t.

Moreover, a writer’s habits with regard to metaphor (and figurative language generally) were key to their entire worldview. Heavy users of figurative language, she said, see the world as interconnected, full of unseen ties and parallels. Whereas those who abstain from figurative language think that the world is made up of discrete things: every situation is exactly itself. (When I read back through my own fiction, I find that it’s just a bunch of metaphors, strung together loosely with a plot. Do I believe that the world is interwoven, weblike? I have no idea, but, if the professor was right, then I guess I do).

That’s the quiz. Are you a heavy user of metaphor, or not? Now you know which kind of person you are.

2.

My professor’s division of the world was pretty morally neutral. It’s not immediately clear, whether it’s superior to see the world as interconnected or to see each event as discrete. But of course many people are suspicious of metaphor, and think it’s rhetorically unhelpful or even dishonest. In Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes names four “abuses” of speech, the second of which is “when [men] use words metaphorically; that is, in other sense than that they are ordained for; and thereby deceive others.”

On first encounter I found Hobbes’s whole argument sort of obviously silly. The problem is, unfortunately, I also think he might be kind of right. It pains me to say so. My heart lies with the metaphorical and the figurative. I guess I think life is probably not worth living without metaphor. And yet. Think of Trump calling people invaders and parasites. Think of Hitler calling people rats and vermin. It does sometimes feel as if political metaphor is always used for evil, substituting vague impressions and superficial parallels for actual truths, prioritizing what Hobbes would have called “enthusiasm” over reason, and fueling animal impulse at the expense of harmony or truth.

3.

A lot of people, even if they have no particular affection for the political philosophy of Thomas Hobbes, are uneasy with metaphor. Many of the most offensive words and phrases in our language are figurative. Take slurs lobbed at women. Bitch—Metaphor. Cunt—Synecdoche, or Metonomy.1 Then again, a lot of the nicest things you can call a person are figurative, too. Angel. Sweetheart. Honey. My mother used to call us little merry sunshines. Figurative language has an emotional power that the literal lacks. Which is weird, isn’t it? Precise, unambiguous language, language that means exactly what it says, feels staid or even impotent. But calling something by some other thing’s name cuts right to the quick, unlocks a whole new type of emotional response. Another point for Hobbes, I guess.

4.

One problem with the Leviathan argument, however: Hobbes can’t stop using metaphor.2 He writes that

“The Light of humane minds is Perspicuous Words…And on the contrary, Metaphors, and senslesse and ambiguous words, are like Ignes Fatui; and reasoning upon them, is wandering amongst innumerable absurdities; and their end, contention, and sedition, or contempt.”

I can count three metaphors here, without even looking very closely. One assumes that Hobbes was aware of the irony. Maybe he’s trying to slyly demonstrate the problem with metaphor, by using it.

5.

It’s hard to denounce metaphor without using a metaphor. In general, it’s immensely difficult to actually write or speak without figurative language. Language is metaphor and metaphor is language, for better or for worse.

Even while denigrating it, Hobbes does write that metaphor is at least one of the lesser abuses of language, because metaphors “profess their inconstancy”: they are honestly dishonest. You know when you’re seeing a metaphor, and understand intellectually that it’s not the literal truth. But he was wrong. Most metaphors in our speech don’t announce themselves. They’re woven right in, so that we don’t even realize they’re there.

6.

Argument is war, time is money, status is height.

“Most people think they can get along perfectly well without metaphor [...] we have found, on the contrary, that Metaphor is pervasive in everyday life,” write George Lakoff and Mark Johnson at the start of their seminal3 Metaphors we Live By.

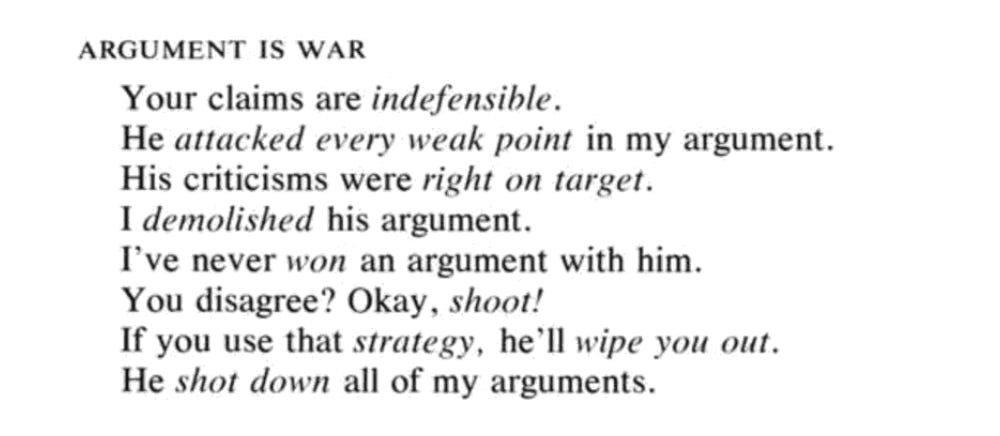

In English, Lakoff and Johnson say, we talk about argument through the framework—the “conceptual metaphor”—that argument is war. Among the examples they list: “He demolished my argument.” “I’ve never won an argument with him.”

Meanwhile, time is money. “You’re wasting my time,” “He’s living on borrowed time.” We also metaphorically map a huge variety of concepts onto the directions Up and Down. To give an abridged list: health (“rose from the dead”/ “his health declined), happiness (“high spirits”/ “depressed”), consciousness (“wake up”/ “fall asleep”), status (“upward mobility”/ “bottom of the hierarchy”) and the future (“upcoming event”/ “back in the day”).

(This is specifically in English—in other languages, for instance, the future is behind you, unseen, and the past visible in front of you. Still a metaphor, of course).

To bring the conversation back to literary language for a moment, Susan Sontag notes that “practically all metaphors for style amount to placing matter on the inside, style on the outside.” In other words, we can’t even talk about whether a writer uses metaphor without using metaphor.

7.

Metaphors aren’t just collaborations between words. They’re in the words themselves. There are different processes by which a word can enter a language. For example, you can add certain prefixes and suffixes, turning “liquid” into “liquidate” or “liquify” or “liquidity.”4 You can borrow from another language—much of our English vocabulary is borrowed from French and Latin. You can squish words together into a compound, or clip them into an abbreviation.

And then, among those other processes, as fundamental as anything else in human language, is metaphor, and its close figurative sibling, metonymy. Table leg. Computer mouse. “I see,” in the sense of “I understand.” For that matter, “Understand,” which probably emerged from a figurative Old English expression meaning something like “Stand among/between.”5 A drinking glass—an object made out of glass. Or “chicken,” the food—a substance made out of chicken, the bird. To grasp a concept. To love ardently. To think hard, or listen close. I could keep going forever. (To go, metaphorically).

8.

We usually think of heavily metaphorical writing as additive, but what if we thought of less-metaphorical writing as subtractive—a process of restriction in the vein of George Perec’s La Disparition, which famously contains no instance of the letter E?

Would it be possible to write a book with no metaphor at all? It feels more like a Borgesian concoction than like a truly feasible stylistic choice.

9.

So let’s turn our attention back to the personality quiz that started us off, back to the question of literary style. Generally, we think of an “unadorned” literary style as one that incorporates minimal figurative language. Carver. Hemingway. Jhumpa Lahiri, whom I adore. Ernaux, in what I’ve read of her. Sally Rooney. These writers of course use figurative language, but they do so, to varying degrees, sparingly, and they are considered stylistically conversational, or else stark, even naked. Here’s a passage from Rooney’s Normal People, picked more or less at random, just for illustration:

He feels his ears get hot. She’s probably just being glib and not suggestive, but if she is being suggestive it’s only to degrade him by association, since she is considered an object of disgust. She wears ugly thick-soled flat shoes and doesn’t put make-up on her face. People have said she doesn’t shave her legs or anything.

Or Lahiri. This is from Interpreter of Maladies.

At the tea stall Mr. and Mrs. Das bickered about who should take Tina to the toilet. Eventually Mrs. Das relented when Mr. Das pointed out that he had given the girl her bath the night before. In the rearview mirror Mr. Kapasi watched as Mrs. Das emerged slowly from his bulky white Ambassador, dragging her shaved, largely bare legs across the back seat.

Meanwhile, it’s the writers who use a lot of metaphor that we think of as departing from ordinary modes of speech into an extravagant or rarefied or experimental literary register. Morrison springs to mind. So does my very favorite, Calvino, in whose work it can be hard to determine exactly where the metaphor ends: maybe it’s all metaphor with no bottom. Woolf—here’s another random passage, from To the Lighthouse, packed with metaphor and simile and personification.

So loveliness reigned and stillness, and together made the shape of loveliness itself, a form from which life had parted; solitary like a pool at evening, far distant, seen from a train window, vanishing so quickly that the pool, pale in the evening, is scarcely robbed of its solitude, though once seen. Loveliness and stillness clasped hands in the bedroom, and among the shrouded jugs and sheeted chairs even the prying of the wind, and the soft nose of the clammy sea airs, rubbing, snuffling, iterating, and reiterating their questions…

And Morrison’s Beloved:

Teeth clamped shut, Denver brakes her sobs. She doesn't move to open the door because there is no world out there. She decides to stay in the cold house and let the dark swallow her like the minnows of light above. She won't put up with another leaving, another trick. Waking up to find one brother then another not at the bottom of the bed, his foot jabbing her spine.

People use words like spare and dry and matter-of-fact to describe writing with fewer obvious metaphors, whereas writing with lots of obvious metaphors get adjectives like flowery and ornate and even poetic, the implication being that the latter is less natural, less like plain old language and more, somehow, like Literature.

10.

But if metaphor is a basic building block of human thought and speech, then it isn’t altogether right, to say that less metaphor-laden speech is somehow less adorned or stylized or literary. All speech is metaphor-laden. It’s just that the metaphors in certain writers’ work, like Woolf’s, tend to announce themselves, while the metaphors in Lahiri’s or Rooney’s or Hemingway’s do not. Consider the passage I cited from Normal People. “if she is being suggestive it’s only to degrade him.” This use of the word degrade is metaphorical, emerging from the conceptual metaphor that Down=Lower Status. And “object of disgust,” too—the original sense of “object” was, basically, “thing,” and it only came, through a metaphorical process, to mean “focus” in the way Rooney is using it.

Or in the Lahiri: “he had given the girl her bath..” The giving is metaphorical, it’s just such a conventionalized metaphor that we don’t see it as such. “Bickered about”: in Old English, “about” was a spatial term, meaning roughly “in the vicinity of,” and only later did it acquire the metaphorical, abstract sense of “relating to.” And what is it they’re bickering about? They’re bickering about who should take the girl to the toilet, a word that once referred to a piece of cloth, and then went through a rollercoaster of semantic shifts driven largely by metonymy, eventually coming to refer to a room containing a commode, and then, euphemistically, figuratively, to the actual technology itself.

What I’m saying is that even writers who aren’t prone to metaphor are still prone to metaphor. The metaphors of Woolf and Morrison “profess their inconstancy,” to put it in Hobbes’s words, but those of Lahiri and Rooney do no such thing. Looked at in this light, then, highly metaphorical speech really might be more honest, less stylized. It unabashedly reveals the hidden core of language itself, the processes behind the material.

Meanwhile, a literary style in which every metaphor is tucked away disguises those processes, and implies that it’s possible for language to be literal at all—for each word to mean what it means, for there to exist some real constancy of signification. It’s a fanciful idea, disguised as sober starkness. We’ll never get away from the figurative. If we resent metaphor, it’s because we live in it.

In poets’ terms, it’s synechdoche, but linguists uses the word “metonymy” as an umbrella term to refer to both devices.

In this way he’s like Plato, whose dialogues attack the corrupting influence of poetry and yet—as Ben Lerner writes—“are themselves poetic - formally experimental imaginative dramatizations[...]Plato is a poet who stays closest to poetry because he refuses all actual poems.”

Metaphor!

At the risk of going down a rabbithole, you can also make a word through something called “zero derivation,” in which a word gains a second meaning without changing form at all. The adjective meaning of “liquid,” or the plural meaning of “fish,” for example. Language is silly!

Stand among and not “stand under,” which is confusing.

i loved this piece and found it really fascinating. the only thing i wanted to note—

you say: “Precise, unambiguous language, language that means exactly what it says, feels staid or even impotent. But calling something by some other thing’s name cuts right to the quick, unlocks a whole new type of emotional response. Another point for Hobbes, I guess.”

i disagree (mostly with hobbes), if the point is for his argument that metaphors are dishonest. isn’t language that can evoke a specific emotional reaction that “plain” language can’t communicate the most honest of all? e.g., if you say, “i love her very much” that might not mean much. but if you say “loving her makes my day brighter, my soul sing” etc etc, that IS more honest, if it actually succeeds at evoking the feeling you feel. we need metaphors precisely because we are trying to be honest, to communicate the depth and breadth of feeling, that plain language fails at capturing.

There are fewer people in history that I would fight as hard as I would fight Hobbes about most things.